Unpacking (trans)gender roles at the Miss America pageant

How a pageant showcased a certain kind of woman and its impact in my own life

While scrolling on Instagram a few weeks ago, a post stuck out to me. Queer journalist Nico Lang (@queernewsdaily) posted about how the Miss America Organization added, and then promptly deleted after receiving backlash, “natural born woman” (whatever the hell that means) to its eligibly requirements, restricting transgender women from participating in the competition. The post linked to an open letter signed by the LGBTQ+ candidates, which calls for all women to compete. The organization hasn’t responded to the demand.

I haven’t been able to stop thinking about this news. What has me fixated on this news is what the Miss America pageant has represented.

It’s not at all surprising to hear about this cultural institution of its own barring trans women. This isn’t the first time, either. In 2018, when Miss America announced they’d discontinue the swimsuit portion of the competition, “natural born woman” (seriously what the fuck) was listed in their eligibility requirements, reports Refinery29.

Before I proceed, there are some points I’d like to make clear. I cannot speak for transgender women nor even other nonbinary people. While gender greatly influences my experience as a trans person, I recognize my view isn’t the only valid one on this issue. I’m also not interested in critiquing LGBTQ+ contestants of Miss America-affiliated pageants. Lastly, I’m not interested in debating whether Miss America or beauty pageants should or shouldn’t exist.

I am interested, however, in interrogating the history of the Miss America Organization critically and analyzing its impact on gender. I’ll also apply critical family history to discuss how Miss America impacted my childhood, drawing from my mother’s upbringing living near Atlantic City. In the journal Genealogy, Professor Dr. Christine E. Sleeter describes critical family history as a “process of situating a family’s history within an analysis of larger social relationships of power, particularly racism, colonization, patriarchy, and/or social class.”

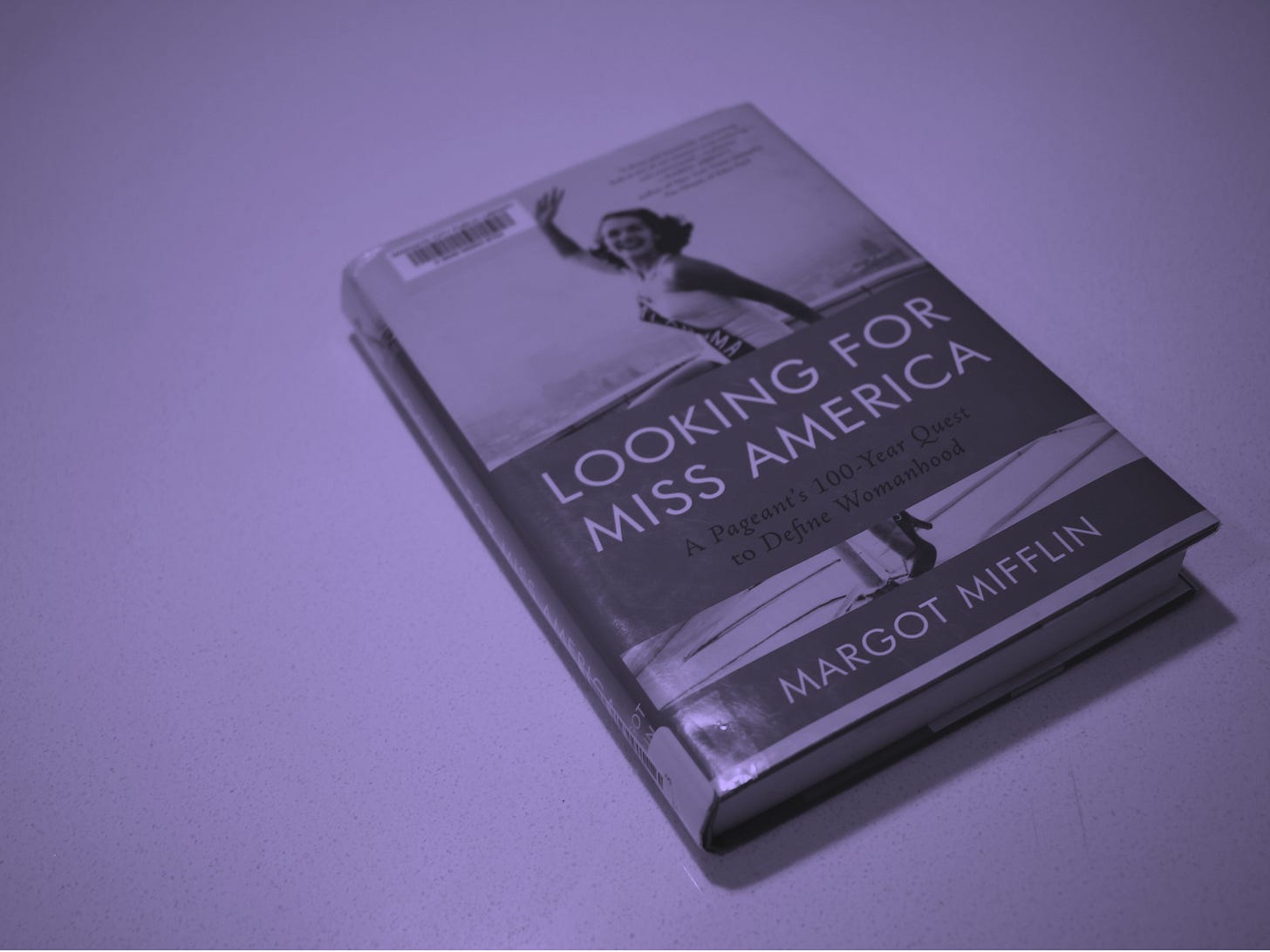

During pivotal social movements for racial and gender justice, the Miss America pageant put the spotlight on a certain type of woman. In 1921, 15-year-old Margaret Gorman became the first Miss America, which at the time was exclusively a swimsuit contest. According to Looking for Miss America: A Pageant’s 100-Year-Quest to Define Womanhood, written by journalist Margot Mifflin, Gorman stands as the smallest crown winner in the pageant’s history. She’d mimic the infantilized archetype the pageant planned to prop up. She possessed the qualities of a particular type of woman: white, unmarried, childlike, childless, thin, cisgender, heterosexual, and able-bodied.

As the pageant promoted a traditional image of a woman, the emerging flapper style—which challenged gender norms with bobbed hair and short dresses—flourished among young women. It’s also not a coincidence—at least in my opinion—that the pageant was founded shortly after (mostly white) women won the right to vote in 1919. Mifflin elaborates about another political movement that’d influence the pageant’s creation:

“The momentum of the American eugenics movement of the early twentieth century had inspired Better Baby contests, which applied the principles of evaluating livestock to children and led to Fitter Family contests nationally, the first of which was held at the 1920 Kansas State Fair. Competing clans were graded on their physical and psychological health and—significantly—heredity, in the name of ‘better breeding’ and building larger families as urbanization shrank American farm communities and immigration complexified national identity. Miss America concentrated the focus: what better way to gauge national fitness than through a contest measuring the quality of the breeders themselves—healthy, young unmarried white women? In the early years, contestants were even introduced with recitations of their genealogical history and ‘breeding,’ tracing their pedigree back for generations.”

Based on the Miss America organization’s roots, it’s not surprising to hear anti-trans eligibility requirements. Though the competition has been around for a literal century, little has done to undo or divest from its colonial history. Even decades later, the pageant would counter any social progress.

On April 6, 1961, my grandmother gave birth to mother in their family home in Ventnor City, New Jersey. Ventnor sits on the eight-mile-long Absecon Island along with Margate City, Longport, and Atlantic City. Growing up on the same island, she’d witness the phenomena of the Miss America pageants every year. My mother was born into an era of Civil Rights and free love, one of iconic rock music and liberatory action. Yet, similarly to the 20s, Miss America continued to mimic the status quo of patriarchy and white supremacy.

The competition had opponents in the women’s liberation movement. As I wrote in a 2018 article for Teen Vogue, the 1968 Miss America pageant served as a backdrop to a historic demonstration led by a small group of women’s lib activists. Protestors opposed the pageant for its “Mindless-Boob-Girlie symbol” and “Madonna Whore image of womanhood” by placing “women on a pedestal/auction block to compete for male approval,” explains W. Joseph Campbell in Ten of the Greatest Misreported Stories in American Journalism. This protest introduced the stereotype of the “bra burning feminist” into cultural lexicon; while some bras were set on fire, it only happened briefly, and bras weren’t the only items burned. In the so-called Freedom Trash Can, protestors also burned girdles, high-heeled shoes, false eyelashes, and magazines such as Playboy and Cosmopolitan. Even today, invoking the image of the “bra burning feminist” is used to discredit feminists.

Additionally, the pageant continued to perpetrate racism. Though the pageant seized its practice of accepting only white contestants in 1940, it wasn’t until 1970 where Cheryl Brown, who’d won a state title in Iowa, would compete as the first Black woman in the national Miss America pageant. It also wasn’t until 1984 where Vanessa Williams became the first Black woman to win the national title, only to resign—the first Miss America to do so—mid-year following the Penthouse Magazine nude photo scandal.

I was exposed to the Miss America organization early. At five years old, I accompanied my mom to Miss Cape May County rehearsals where she’d curate props, many of which were elaborate. The competition would require months of planning leading up to the actual night. As a homemaker who couldn’t hold down a job of her own, this planning consumed her year-round and gave her purpose, even under extreme stress.

I’d witness firsthand how Miss America projected a certain kind of womanhood onto me amidst the W. Bush administration, despite ongoing counter cultural anti-war movements. Unlike the Miss Universe pageant, Miss America is often poised—at least to those involved within the organization—as more sophisticated for “well-rounded” women who are both beautiful and talented, both pretty and smart. I still recount watching the talent portion of the 1999 competition. I watched a contestant, who’d later be crowned the winner, play the flute and illuminate the whole room. The entire performance hall of the Ocean City Convention Center clapped along to her song. I was absolutely blown away. I believed that I, too, could one day play the flute and compete myself. First, though, I had to be pretty. To deserve time on the stage, I’d have to conform to a certain kind of femininity. I had my destiny already chosen for me: to be judged based on my feminine appearance.

I’d never go on to compete in a beauty pageant. By the time I was a teenager who was more interested in lucid dreaming than evening gowns, my mom threw away her beloved beauty queen dreams of me (and likely dreams of her own, by proxy). I was already dressing androgynously as a closet queer kid and wasn’t looking back.

My exposure to Miss America was one of the many ways my mom projected femininity onto me. I was expected to play the role of the contestant. Given the time and place my mom grew up in, too, I anticipate these gender roles were projected onto her, even if it were unconscious. My mom certainly wasn’t the first woman to grapple with toxic femininity, yet it’s a legacy passed down I’m left to heal from. Diving into the history of Miss America has been so eye-opening, and even relieving, to learn where this Gender Stuff between my mom and I originated from. It’s certainly not the only source of toxic gender norms, but it’s a rich relic to reflect on, especially as a nonbinary person with Gender Feelings.

Dear reader, I promised you reflection questions each newsletter to consult your journal, tarot cards, spirit guides, Voice Note app, etc. Much of this edition was focused on my personal experience, so I don’t expect this to be super universal—although if it is and you’d like to share your experience, please reach out and let’s talk! If it doesn’t, let’s then focus on toxic gender norms we’d learn by observation. As always, if you feel comfortable, reply to this email or comment on this post with your answers. I’d love to hear from you!

Growing up, were you exposed to cultural institutions that reinforced toxic gender norms? If yes, how did it impact you looking back?

Were there any cultural relics local to your neighborhood or community that reinforced toxic gender norms? If yes, how did it impact you looking back?

Once you begin to identify where you learned toxic gender norms, what steps can you take (or have already taken) to unlearn them?